Alan Moore, where his childhood home in Northampton’s Boroughs once stood. Photo: Dominic Wells

I recently spent six hours with Alan Moore. We went on a walking tour of his old Northampton neighbourhood, and stood where his childhood home once stood (pictured above). We discussed Anonymous, Brexit and the nature of time. And Moore revealed how very much more than you might realise in his extraordinary new novel Jerusalem is fact – including a dark family secret which he reveals here for the first time.

This is a longish feature. It needs to be. But it’s nowhere as long as the interview transcript – edited highlights of which I shall release online over the coming days, starting here. So settle down with the stimulant of your choice, abandon your preconceptions, and step into the Mind of Moore.

It’s 1986…

Watchmen is nearing the middle of its 12-issue run. It’s clear already that it’s something special. This ambitious, intricately structured deconstruction and resurrection of the superhero genre has stoked the fame of its writer, Alan Moore, to such fever pitch that at conventions autograph-hunters pursue him even into the toilet. Yet he still finds time to speak to a young journalist with a monthly comics column in London’s Alternative Magazine.

“It’s about time people stopped debating whether comics are art,” Moore tells me combatively, “and just get on with making good art.”

Watchmen will later be the only graphic novel placed on Time magazine’s list of 100 greatest novels, and will create a surge in intelligent comics, which itself will create a surge in comic-book movies, leading to today’s overpowering dominance of the big screen by men and women in spandex. In that sense, Moore is probably the most influential living British writer. Moore will reject the monster he has created, but for now…

In the issue of Watchmen just published when we speak in 1986, a nuclear scientist acquires superpowers and becomes “Doctor Manhattan”. It’s one of those convenient radiation accidents common to the comic-book genre, but Moore does something much more interesting with the trope than turning his hero into a square-jawed do-gooding protector of mankind like Superman. If a man became, effectively, a god, wondered Moore, would he still have anything in common with mankind?

So instead, Moore’s superhuman drifts existentially out of our orbit – indeed, outside of conventional chronology altogether. In an astonishing tour de force, the panel captions of this chapter keep shifting backwards and forwards as we are shown time through Doctor Manhattan’s all-seeing eyes – not as a linear progression, but as past, present and future all happening simultaneously: “It’s October, 1985. I’m on Mars. It’s July, 1959. I’m in New Jersey, at the Palisades Amusement Park…”

Page from Watchmen. Writer: Alan Moore. Artist: Dave Gibbons. © DC Comics

Neither Moore nor I can know, in 1986, that 30 years later this remarkable notion will have inspired his masterwork, a 1,200-page novel called Jerusalem. But before we meet to talk about that (or is that simultaneously?) our timelines will criss-cross a few more times…

It’s 1996…

“I continually monitor the possibility that I might be going mad,” says Moore. In a London wine bar, we are discussing his first “proper” novel, Voice of the Fire, for a feature in Time Out; the magic rituals that now fuel his creative writing; and the bizarre coincidence that, after he’d written about a dog padding through the streets of Northampton with a severed human head in its jaws, this actually happened in real life. “Did I intuit that, or did I somehow will it into being?” he muses.

It gets weirder. In 20 years’ time, when we meet yet again to talk about his novel Jerusalem, I will recall this earlier chat and see in it another cosmic coincidence. The bar we are sitting in, in 1996, is also called… Jerusalem.

It’s 1989…

At a gigantic comics festival in France, Alan Moore and artist Melinda Gebbie are showing me panels from their nascent joint venture, Lost Girls. Refusing to describe the graphic-novel-to-be as “erotica”, preferring the more honest and working-class label of “pornography”, Moore brings together Alice from Wonderland, Dorothy from Oz and Wendy from Neverland in a pastel-coloured mosaic of polymorphous perversity that won’t be published in full until 18 years later.

And what of Melinda Gebbie? Reader, in 2007, she married him.

Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie’s wedding. Photo: Neil Gaiman, from his blog

It’s 2002…

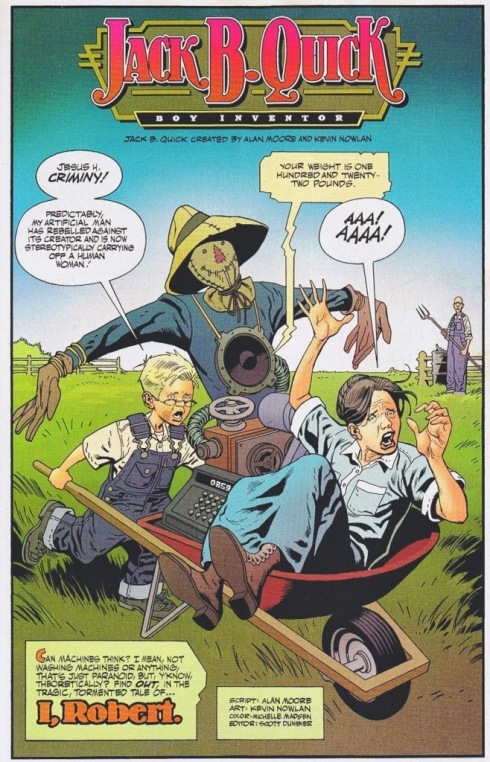

The idea Moore had in Lost Girls of plucking established fictional characters from the straitjackets of their original novels and mixing them together has blossomed into The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, a series of comics featuring Captain Nemo, the Invisible Man, Dr Jekyll/Mr Hyde and Virginia Woolf’s gender-fluid Orlando.

“This planet has a physical geography with which we have already familiarised ourselves,” Moore is telling me, for a feature in The Times. “But since the dawn of the first stories, there is a fictional geography, where the gods and demons live. We have created this big imaginary planet that is a counterpart to our own; and in some cases these places are more familiar to us than the real ones.”

However, the Hollywood adaptation being shot without his approval as we speak will cause him to disown all films based on his work – signing over all his royalties to the illustrators instead. The price of principle must run into the millions of pounds: as well as the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, films of his work will include From Hell, Watchmen, V for Vendetta, Constantine, and Batman: The Killing Joke.

It’s 1990…

Moore has rejected the superhero genre he helped to revive. Instead, he’s just released the first issue of Big Numbers – a Northampton-set 12-part comic inspired by Chaos Theory and structured like the endlessly regressive fractals of the Mandelbrot Set. His small ambition, he tells me in his surprisingly normal-looking Northampton living room, is to “re-integrate all the shattered fragments of our culture”, fusing “maths and art, politics and economics”.

Esoteric, yes, but such is Moore’s following that its first issue still sells 65,000 copies. However, after two successive artists buckled under the pressure of illustrating it, Big Numbers never reaches issue 3. Moore’s fledgling self-publishing imprint collapses, as does his polyamorous relationship with the two women he lived with: his wife Phyllis Moore and their lover Debbie Delano.

It’s 2013…

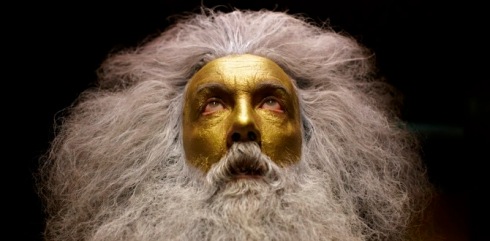

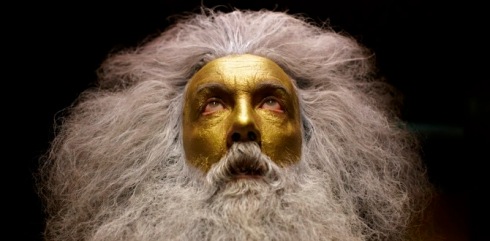

Moore may have rejected Hollywood, but he’s not above creating films on his own terms. In the ‘80s, he wrote a screenplay for Malcolm McLaren called Fashion Beast, and now we’re at a screening and Q&A for Show Pieces, a feature-length series of short films written by Moore, in which he plays a compere in a gentleman’s club of the afterlife who is, effectively, God: striking gold face-paint, snow-white hair and killer Cuban heels.

© 2012 John Angerson. Filming of Jimmy’s End – Northampton

“I felt I’d more or less exhausted what I could do with my work while remaining in the boundaries of strict rationality,” Moore says after the screening, explaining why he first began practising magic. “One problem with art at the moment as I see it is there is nothing visionary, nothing magical, nothing of the numinous. I believe art is magic and magic is art.”

It’s the afternoon of July 9, 2016…

Thirty years from our very first meeting, at least in the linear fashion in which humans perceive time, Alan Moore and I are holed up in an Italian restaurant in Northampton to discuss the culmination of a lifetime’s work, research and philosophy. “Bigger than the Bible and I hope more socially useful”, is how Moore describes his sprawling magnum opus, Jerusalem, with his customarily deadpan humour.

His Father-Christmas-meets-heavy-metal-roadie’s beard is a little greyer than it once was, the rings on his fingers more ornate, but Moore hasn’t lost the Northampton accent which turns every “I” into an “Oy”, nor the astonishing verbal felicity with which his every sentence emerges fully formed, sub-clauses and all. It’s as though he were writing rather than speaking; or as though he already knows how each sentence will end before he embarks upon it.

Deep into our six-hour talk, somewhere around the dessert (three scoops of ice cream for Moore, hold the whipped cream), the Sage of Northampton is explaining how he came to see the world as Doctor Manhattan does. In 1994, he experienced an “absolute, crystalline understanding” during a magical ritual. Since then, Moore has believed, as Einstein supposedly did, that time is a solid in which our lives are embedded; it is only our perception of it which makes it appear linear.

In other words, everything that has ever happened is still happening. Everything which is about to happen has already happened. We never truly die: the lives we are living now are solid and eternal. That’s all major religions out of business, then.

“The thing is,” says Moore, “we don’t have free will, or at least that’s what I believe, and I think most physicists tend to think that as well, that this is a predetermined universe. That’s got to pretty much kill religion because there aren’t any religions that aren’t based on some kind of moral imperative. They’ve all got sin, karma or something a bit like that. In a predetermined universe how can you talk about sin? How can you talk about virtue?”

This leads to a humanist philosophy that is not without its own morality, albeit one that this is self-imposed and unique to each individual. It means, says Moore, that you should be careful not to do anything in life that you cannot live with for all eternity.

“We’re talking here about heaven and hell, we’re talking about them as being simultaneous and present, that all the worst moments of your life forever, that’s hell; all the best moments of your life forever, that’s paradise. So, this is where we are. We’re in hell, we’re in paradise; both together, forever. I’m saying that everywhere is Jerusalem. That in an Einsteinian block universe, where all time is presumably simultaneous, then everywhere is the eternal heavenly city.”

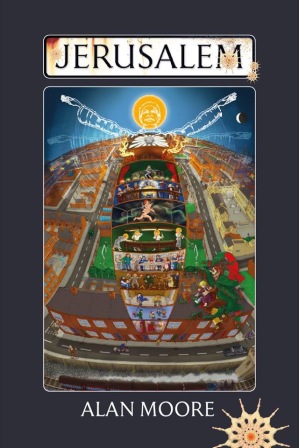

This is why, as in Alan Moore’s first novel, Voice of the Fire, almost all the action in Jerusalem takes place within a small geographical area of Northampton, but ranging across different historical eras, each centring on different protagonists who end up interconnecting in surprising ways. It took Moore ten years to write – in between multiple other projects – and took me three weeks to read. It’s part social history of Northampton, part thinly fictionalised history of Moore’s own family, part philosophical treatise, part rip-roaring adventure in which a gang of kids maraud through the afterlife in a central section Moore describes as like “a savage, hallucinating Enid Blyton”.

Book jacket for Jerusalem. Artwork: Alan Moore

As if that wasn’t hard enough to pull off, Moore adapts his writing style to the inner voice of whoever is the chapter’s focus. One is written as a play, in the style of Waiting for Godot, and throws together the spirits of Thomas Becket, Samuel Beckett, John Clare and John Bunyan – all of whom have some connection with Northampton – as they observe and comment on a husband and wife wrestling with a terrible family secret… but more of that particular revelation later.

Another chapter, described from the point of view of James Joyce’s mad daughter Lucia who was institutionalised for 30 years in a Northampton mental hospital, is written in a mangled, pun-filled gibber-English as a homage to Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. It was so laborious to compose that Moore took a year’s break after finishing it.

If this makes Jerusalem sound like hard going, it isn’t. It’s gripping, full of stylistic fireworks, frequently laugh-out-loud funny, sometimes terrifying, occasionally frustrating. Could it have been shorter? Of course. But it’s the digressions and bizarre connections that make the book, the nuggets of pure gold that Moore has sifted from the silt of local history through prodigious research and banked in his near-photographic memory.

“Nearly everything is historical fact,” says Moore, before deadpanning: “I’d take all the angels and demons with a pinch of salt. A lot of it is actually 100 per cent materially true, but I think all of it is emotionally true. And also we are not just our bricks and mortar, we are not just our flesh and blood, we are not just our material components. Everything in our world has got an imaginary component. As individuals, we’re always telling people the legend of us. The same goes for our houses, our streets, our towns, our country – there is a huge imaginary component to human life and if in the interests of scientific realism you ignore that, you are not describing reality.

“But science cannot measure the bit that isn’t material. Science is a brilliant tool for analysing our material universe, but science cannot talk about what is inside the human mind: it’s beyond the realm of proof, it’s beyond the realm of science. So I say they should be left to art and magic, which are pretty much the same thing.”

One of the most moving aspects of the book is how Moore exhumes the oral working-class history of Northampton, resurrecting and giving voice to those who had none when they lived, such as a homeless teen who died of exposure, whom Moore makes a key character, or “Black Charley”, who emigrated to Northampton from America. Even the colourful vignette in Jerusalem about a half-drunk zebra tethered outside a pub is based on historical fact.

“Yeah, that’s true,” confirms Moore, “Newton Pratt had got a zebra, which he used to keep tied up on Sundays when he went to the Friendly Arms, and bring it out a half of beer, so there would be this drunk zebra half way up Scarletwell Street. You know – these are the things that need to be preserved. Because they are wonderful. And yet, who cares?

“These things must have happened in every little deprived area, all across the world. But we’re not interested in deprived areas, it’s got to be the history of Church and State and Monarchy – that’s the only history that counts, apparently. I would say that’s the only history that’s simplistic to keep track of.”

Researching all this was a Herculean task, which continued throughout the writing of the book. In fact, it wasn’t until the closing chapters that he discovered a previously unknown link between a key piece of industrial history and the hymn that gives the book its name…

It’s midday on July 9, 2016…

Before we go for lunch, Moore takes me on a walking tour of Northampton’s Boroughs. This is the area in which Moore grew up, and which forms the geographical boundaries of Jerusalem. I’m instructed to walk on his right: he’s nearly deaf in his left ear. He carries a cane, but doesn’t seem to need it; in his hands it seems more wizard’s staff than walking aid. He is slightly stooped, but not from age – it’s the life-long stance of one accustomed to being the tallest person in the room.

Down a canal tow-path near Northampton station, he shows me what he describes as “the original dark Satanic mill”, as sung about in William Blake’s hymn, Jerusalem.

Alan Moore at the remnants of the original dark satanic mill. Photo: Dominic Wells

“Here it was,” Moore says, pointing to an unprepossessing stone wall underneath a bridge that’s so low that he has to stoop. “That’s where industry and free-market conservatism were born. It [the machinery] was driving three looms, these looms would work without anybody to look after them, they’d just employ a few children to sweep out the corners and unsnag the machines if they got snagged, and immediately of course all the local cottage industries collapsed.

“So a little while after that, Adam Smith came to visit and he saw these machines working with nobody to work them, and he said ‘oh that’s marvellous, it’s like there’s a hidden hand’, then ‘ooh, that would make a nice metaphor for freemarket capitalism’. And that’s why we have this completely mystical notion that doesn’t exist, this is why Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher said that it was OK to deregulate the banks; we didn’t need market control because there was hidden hand! And now here we are.”

It’s a strange experience, walking the streets with this bearded compendium of knowledge. Every corner provokes a reminiscence, such as the graffiti which he recognises as the work of Bill Drummond of art-pop group the KLF, who came round to his house to show him the film of them burning a million pounds. Do they regret it now, I ask?

“It’s not so much that they regret it, but I think it haunts them. I heard a brilliant definition of haunting: ‘That which haunts us is that which we do not or do not completely understand.’ And I thought, that makes sense. Often we don’t understand our own actions. And certainly, if we’d gone to the Isle of Jura and burned a million quid, we would have a lot of questions!”

Further on, we pass the Black Lion pub, where Moore was photographed in a pram as a baby; a war memorial with his uncle Jack’s name on it, in the grounds of a church built when this was the centre of Mercia, which was the centre of England, and which “would have been visited by Samuel Beckett when he was on a church crawl, while all his cricketing mates were off drinking and whoring”; a wooden statue of a medieval knight in armour, part of new tourist initiative called the Knight’s Trail, which provokes the wry observation, “You know, at the present time, probably putting up celebratory statues of people who are only famous for killing Muslims is not the best idea, I wouldn’t have thought. But that’s Northampton council.”

And then, round a few more bends, “That’s it,” says Moore, “that’s my bedroom.”

And with that, Moore mimes walking up some stairs and stops still, spreading his arms to indicate, here: this spot. As in the poem Ozymandias, nothing beside remains. The house of his birth is long gone, along with the 20 others like it that used to line this now benighted stretch of Northampton roadside; and yet it also lives on – in the past, and in Moore’s mind, and now in his 1,200-page magnum opus.

And how does it feel, to be standing here, on the spot where his childhood self once slept? Moore pauses. “Haunted,” he says simply.

There are ghosts aplenty in Jerusalem, and we stumble across a ghost story of our own, on our walking tour of Moore’s old neighbourhood. We’re inspecting a strange bolted door to and from nowhere on the first floor of Nonconformist leader Philip Doddridge’s church, which Alan Moore in Jerusalem reimagines as a gateway to a fourth-dimensional afterlife world, when a voice pipes up from across the street: “What do you think that door there’s for?”

Philip Doddridge’s door to nowhere. Photo: Dominic Wells

Moore crosses the street to address the stranger, an ill-shaven rough-sleeper of about 40. “I think it’s got supernatural origins, that’s my theory,” says Moore, happy to chat to anyone about the strange and unusual. “We’re putting that on the cover of the book I’m doing. One of the paperbacks has just got that, with a bolt halfway up the wall.”

Homeless man: “It doesn’t make sense, does it?”

Moore: “There’s a lot of stuff in Northampton that doesn’t.”

Homeless man: “Yeah. To be honest with you, I’m an alcoholic, but I’ve cut it right down to a couple a day, and a couple of days ago… I don’t believe in ghosts, but I saw a woman walking, and just – out of the corner of my eye, and I looked, it was in the rain and I was going to say what are you doing in the rain, and she just… went away. There was nowhere for her to go.”

Alan Moore is so enrapt by this story that he’s unconsciously taken several small steps towards the man, and is leaning in to catch every word. I’m starting to understand that Moore is some sort of Weirdness Magnet.

Moore: “This area is full of ghosts, and actually, being a bit pissed helps to see them. I believe it. It’s why there were so many of them in pubs. All the pubs round here had at least two or three, when I was a kid. So, the pubs have been pulled down, where else have they got to go? Out in the rain with you, eh?”

They chat for a while, the homeless man and the super-successful author who only looks like he could be homeless, about the supernatural and the history of Northampton. Then, in an echo of a scene in Jerusalem so uncanny it makes my head spin, Moore stuffs a crumpled £20 note into the man’s hands.

Moore: “You look after yourself mate, have a good weekend, it’s really nice to meet someone who appreciates the ground they’re standing on.”

Homeless man [suddenly blurts out]: “I enjoyed Watchmen.”

Moore: “Did you?”

Homeless man: “I loved it.”

Moore: “Oh, that’s nice.”

Homeless man: “You and… Gibbon?”

Moore [Northampton accent suddenly stronger in anger]: “Dave Gibbons. Oi hope Oi never see that fucker for as long as Oi live. Oi don’t have a copy of the book in me ‘ouse, but Oi’m glad you got some pleasure out of it, mate.”

Homeless man: “And The Killing Joke Batman, that is a belter.”

Moore: “Well, I threw it out. But glad you liked it, man. Have a good day, won’t you.”

And there, in a nutshell, are the two faces of Alan Moore. On the one hand, he has been so publicly excoriating of Hollywood profiting from his works, and of former friends and co-creators such as Dave Gibbons who he sees as abetting them, that he’s earned a reputation as a grumpy old man: “Get off my lawn, says Alan Moore” was a recent headline in the satirical website Newsthump. On the other hand, he’s unfailingly gracious and loyal to those he feels deserves it.

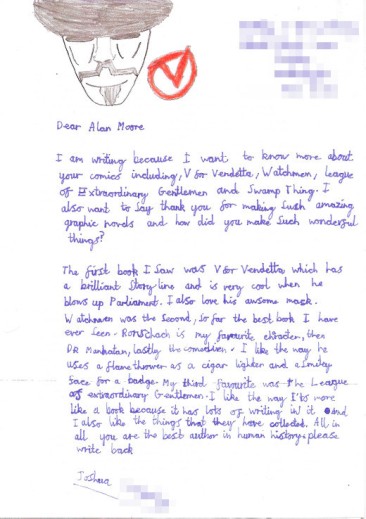

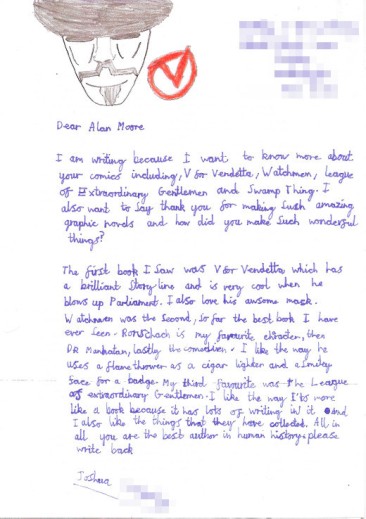

A sweet letter Moore wrote back to a nine-year-old fan who’d called him “the greatest author in human history” recently went viral. (Neil Gaiman, author of Coraline, Sandman and Good Omens, goes one further, dubbing Moore “the Greatest Living Englishman”.) Last year Moore sent a cheque for £10,000 to an old friend, window-cleaner Graham Cousins, whose African wife had fallen foul of Home Office rules requiring a minimum income threshold or savings to live with him in the UK.

To cap it all, during our walk, preposterously (and I swear this happened; none of Moore’s legendarily large “herbal” cigarettes were harmed in the making of this interview), Moore even rescues a child’s balloon. As it soars skywards above the crowded shopping street, before anyone else has time to react, he reaches up on tiptoe with surprising agility to grab its string, and returns it with a twinkle-eyed smile just as the bereft infant was preparing to howl.

“See?” I feel like telling the tiny tot. “Father Christmas is real. He just likes to take mind-bending drugs and worship the false Roman snake-god Glycon.”

Round the next corner, it’s Moore who spots a T-shirt slogan on a passer-by that I’d missed: “I see a lot stranger T-shirts these days than I used to,” he remarks. “Did you see that one? It said, ‘Good morning, I see the assassins have failed’.” And then we’re down some steps and into the Italian restaurant, where the manager greets Moore like a long-lost friend and asks him about his books, and once again…

It’s the afternoon of July 9, 2016…

I’m asking Moore if, in Jerusalem, he’s had a sex change. One of the key characters in the novel is Alma Warren, an artist. Like Moore, she is a reluctant local celebrity; the exhibition of paintings she is staging have titles which match the chapter headings in Jerusalem (very meta); and her hair is described thusly: “She’s learned early in life that if she doesn’t brush her mane once every day it will develop knots that in a week will have turned into impacted rhino horn: bolls of mahogany that it will take tree-surgeons, chainsaws, ropes and ladders to remove.”

Strangest of all, there is a scene in which Alma thrusts a crumpled £20 note into the hands of an impoverished friend she meets on the streets – just like on our walk.

Clearly “Alma Warren” is an alter-ego to Alan Moore. “Yeah, well,” agrees Moore, holding up his hands in surrender, “I mean I had to be in the novel, because otherwise there’s no centre, there’s got to be someone for Mike to be brother of, and various people to be the grandmothers of, but I didn’t want to bring all the baggage of ‘Alan Moore’ to it. So I came up with this woman who my daughters tell me is exactly like me. [My friend] John Higgs said that you are going to read a lot of autobiographies that are nowhere near this personal!”

It turns out many of the key characters in the book are fictionalised versions of Moore’s relatives. Take mad Snowy Vernall who, while retouching the ceiling frescoes of St Paul’s cathedral, receives a terrifying angelic visitation from which he learns the secrets of existence and is winched down again with his ginger hair turned white: he is based on Moore’s great-grandfather Ginger Vernon. Snowy’s equally touched sister, Thursa, is based on another ancestor of Moore’s who used to wander round during the Blitz playing the accordion.

As to the small boy, Mike, who, due to a celestial mix-up, “dies” while choking on a cough sweet and spends the mid-section of the book in the afterlife with the Dead Dead Gang (a name that came to Moore in a dream), he is based on Moore’s own brother, who really did stop breathing for a few minutes as a small child while choking on a cough sweet.

And as for Moore’s great-aunt and uncle… that’s a story with a dark secret that Moore will keep to himself until the day is nearly over.

Meanwhile, there is much to discuss. For instance, how does Alan Moore feel about literally creating the face of not one, but three major counter-cultural youth movements?

In the late ‘80s, the Smiley face badge he had popularised in Watchmen became the emblem of Acid House and the illegal raves of the Second Summer of Love. More recently, the V for Vendetta mask of Moore’s anarchist antihero was adopted by both the Occupy and Anonymous movements.

“Well, how do I feel…” Moore strokes down the errant whiskers on his beard as though they were straying thoughts that must be put in order. “I’m glad that they’ve got it, although – they didn’t get it from the comic, did they? They got it from the film, which I have never seen and which, from a position of complete ignorance, I am willing to describe as a total rat’s abortion. But I’m glad it’s been of use to these protestors, because generally I really admire what they do.”

He met the Occupy protesters who’d camped outside St Paul’s when a C4 news crew took him along. As for Anonymous, the closest he came was when someone claiming to be from the hackers’ collective got in touch saying they were planning a Day of Mayhem based on scenarios in Watchmen.

Alan Moore with “Smiley” riot shield by Jimmy Cauty. Photo: Alistair Fruish

“We got back to them saying, stuff based on comic books, that won’t work; and anyway why are you sending me this? How do I know who you are? In fact, if I was the intelligence services, who had got no idea how to infiltrate the members of Anonymous, because of their anonymity, I might be thinking, why not get somebody who is publicly associated with Anonymous, and get them to sign up to something really stupid, and use that to discredit the entire network? So I said, no thanks.”

It’s a not inconsiderable irony, too, that though V for Vendetta illustrator David Lloyd gets a percentage of the royalties for the mask (Moore having disowned his), mostly the sales from this anarchist rallying symbol fill the coffers of the exceedingly corporate Warner Bros. As for the Smiley face, Moore was recently photographed holding a full-sized riot shield with the famous blood-splattered logo designed by artist Jim Cauty of the KLF, which he says he’s “very proud” of.

The politics of protest is something that gets Moore exercised: this, after all, is a man whose phone was tapped after he was commissioned in the late ‘80s by the Christic Institute to write the graphic novel Brought to Light, based on their extensive research into the now notorious Iran-Contra scandal. Of Brexit, Moore says that “I hadn’t realised how surrounded by idiots I was”, and believes democracy is fundamentally broken.

As an anarchist, he does not vote, but he’s not above the odd direct action – he speaks admiringly of one friend, thinly disguised in Jerusalem, whose many protests included renaming Little Cross Street as Double Cross Street after Northampton’s council had evacuated tenants there for minor repairs, and never moved them back in. The day after the Brexit referendum, Moore himself took to the stage for a piece of political performance art with his face terrifyingly made up as a mandrill. Yes, a mandrill – the bright-blue-and-red-faced relative of the baboon.

What was that all about? Moore smiles conspiratorially: “I can give you the whole thing, if you want.” He leans across the table and, in a deep, urgent and rhythmic tone, starts to recite:

“We’ll march on ugliness and stupidity, we’ll make loveliness compulsory, and the roar of our orchestra engines will soar evermore in a glorious, annihilating symphony, for the tyranny of beauty is our god-given duty: every child at birth is to be issued with a ukulele, given their own flag and granted absolute and utter sovereignty, and as long as it’s coloured in nicely and has an old woman on, make their own currency. Turn every urban address into a dripping Rousseau wilderness. We’ll keep advancing until there’s nobody not dancing. We’ll put politics in the pillory, put the art back in artillery; we can weaponise wonder, and our voice shall be as thunder… Cometh the moment, cometh the Mandrill.”

Alan Moore made up as a mandrill after the Brexit vote. Photo: Amber Moore, from her Twitter

And that’s just a quarter of the spiel. In my time as an interviewer, I’ve had Kim Cattrall ask me to dance, Felicity Kendal show me her new tattoo, Richard O’Brien sing Unchained Melody to me from across a grand piano, and I’ve had to ask David Bowie how he feels to be thought of as a tosser. But to be on the receiving end of Alan Moore’s “Mandrillifesto”, seeing my affable dining companion transform suddenly into totalitarian ape, that’s right up there. At the end of the Brexit performance, says Moore, he was swaying to the crowd, with his followers behind him on stage, in black, with armbands, chanting “Cometh the moment, cometh the Mandrill!”

Funnily enough, this is far from Moore’s first brush with playing at being a Messiah (or, at least, a very naughty boy)…

It’s the morning of July 9, 2016…

Before our walking tour we’re sitting sipping tea from polystyrene cups in Northampton’s brand spanking new railway station, which Moore predictably despises, and only ten minutes into our opening conversation I’m being informed that Alan Moore is God. By Him Himself.

Before he became a full-time writer, Moore’s jobs included purveyor of LSD (for which he was expelled from school), slaughterhouse worker, and working for a gas board sub-contractor while the new town of Milton Keynes was being built. Four decades later, this year, he was doing a spoken performance in Milton Keynes, in which he riffed on an article in New Scientist which speculated that because we will soon have quantum supercomputers capable of holding more particles than there are in the entire universe, we will then be able to simulate an entire universe, including all the life forms in it, which will not know they are simulated.

“And if we’re going to be able to do this,” says Moore, “the odds of this being the first time this has happened are vanishingly small. It is much more likely that we are in a simulation, of a simulation, of a simulation, and so on.”

The programmer of the game, therefore, will be God. And if he is at all like the humans he has created, the article postulated, he will want to put an avatar of himself in the game.

“Now he wouldn’t go for something really obvious, like President of the United States,” explains Moore. “Yet he still probably would want to make himself a special person. So what [the article] was saying is, the best thing to do is to suck up to celebrities because they might be God.”

I interject that I’ve found my story headline: “‘Kim Kardashian is God,’ says Alan Moore!” But he has something better in mind.

“Obviously,” he continues, “you wouldn’t want to suck up to just any celebrity. So what I said was, if I was you, people of Milton Keynes, I would go for a celebrity who sounded, and perhaps looked,” here he strokes his own huge grey beard meaningfully, “the way you might imagine the creator of the universe to look!

“But I said even that’s not enough, because that could have you worshipping pretty much any tramp; so I said, you have to ask yourself, does the person who I’m looking at appear to have physically created the environment around me? And I said, in your case, people of Milton Keynes…” He raises his eyebrows meaningfully, and gestures towards himself.

“So, yeah,” he deadpans. “I am still worshipped as a God by the primitive and superstitious people of Milton Keynes.”

It’s 6pm, July 9, 2016…

Lunch is long finished. The second coffee has been drunk. We’ve talked for six hours in all, including the walking tour, and the interview transcript will run to 30,000 words. But even now, sharing a taxi back to the train station, Moore has one big surprise left in store.

As we near a church, he points out the steps where, in one chapter of Jerusalem, a husband and wife are arguing. The reader gets the impression they’ve been arguing a long time. Forever, it transpires. In Alan Moore’s metaphor for the afterlife, we are doomed to repeat our present actions for eternity. What’s that he’d said earlier today?

“We’re talking here about heaven and hell, we’re talking about them as being simultaneous and present, that all the worst moments of your life forever, that’s hell; all the best moments of your life forever, that’s paradise.”

The couple’s argument is over their daughter, who has been acting up. It emerges that the father has been creeping into her room at night; and the mother, for all her furious protestation, finally admits she tacitly condoned it. Eventually, both agree to hush up the incestuous affair – by shipping the child off to the mental hospital.

It seems, when you read it, a bizarre and twisted leap of imagination – except that Moore reveals, in the back of the cab, that he didn’t make it up.

So let’s be clear, I ask Moore: this story of incest, leading to their own daughter’s enforced institutionalisation to silence her, is based on his own relatives?

“That is true. Yeah.”

Is this known and acknowledged in the family?

“No.”

Won’t this put the cat among the pigeons?

“Most of the people are dead. Uh, and they knew anyway.”

He explains how we was researching his neighbourhood through old Kelly’s Street Directories – which house was owned by whom – and was stunned to discover that his great uncle Jack Vernon and great aunt Celia lived on a road on which the young Moore regularly visited a school friend, and yet no one had told him of their existence.

“They’d been ostracised,” he realised. “They’d been banished. And, knowing my family, that sent a little shudder through me. I thought, shit, that was serious. That was, ‘you are dead to us… we know what you’ve done’.”

He did some digging, spoke to some family members, and pieced together the whole sorry story.

“The book is dedicated to Audrey,” he says. “The whole book was an attempt… an attempt to rescue her? A particularly futile and belated attempt, but the best I could do. The only way that I could rescue her was in a fiction.”

With impeccable timing, the taxi chooses this moment to pull into the train station, its brakes bringing the appalling revelation to a full stop. In a few seconds, we will make our goodbyes, and Moore will switch suddenly back to cheery mode as though a cloud had passed: “See you again with my next book in a decade, when we’re both creaking old.”

But before we do, Moore leans across the black leather seat of the taxi, taps me on the shoulder, and adds, with gravity and unusual emphasis: “People deserve to know.”

Jerusalem is out now in hardback from Knockabout in the UK and Liveright in the US. I am also posting edited highlights from the 30,000-word interview transcript, starting with Alan Moore on Brexit, fixing our broken democracy and comforting Stewart Lee. Follow this blog using the button at top right to receive updates.

Tags: Acid House, Adam Smith, Alan Moore, Alma Warren, anarchy, Anonymous, block universe, Brexit, comics, democracy, einstein, Fashion Beast, film, Finnegans Wake, God, graphic novels, greatest author in human history, interview, Jerusalem, Jim Cauty, Joyce, KLF, long read, Mandrill, Melinda Gebbie, Miltyon Keynes, Northampton, Occupy, Philip Doddridge, review, Show Pieces, Smiley, The Boroughs, time, V for Vendetta, walking tour, Watchmen