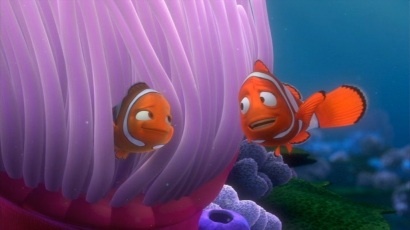

The Rocky Horror royal box at the Albert Hall. Bottom left: Rocky Horror Show producer Michael White with his carer Salem. Middle row, left to right: film-maker Marcus Campbell Sinclair; the inimitable Lady Stephens (“Magenta”), and her ex-husband, director Don Hawkins; Henry Woolf, producer of Harold Pinter’s plays and also the photographer at the start of the Rocky Horror Picture Show, with his wife Susan, a famous coach; and Kevin Whitney, Olympic artist and director of Syd Barrett film Psychedelia. Top row, l to r: artist and Alternative Miss World impresario Andrew Logan; the rock star Adam Ant; talent manager Gregor Gee; architect Michael Davis, who designed the Glasshouse for himself and Andrew Logan. Photo by Sam Mardon.

It’s astounding. Time is fleeting. Can it really be 40 years since The Rocky Horror Picture Show opened? Actually, technically, the 40th anniversary is next year; but with a bit of a mind-flip, we were into the time-slip, and celebrated a couple of months early.

I arrived on a rather special night: yesterday The Rocky Horror Picture Show played at the Royal Albert Hall, on a giant screen, introduced by Lady Stephens, the actress formerly known as Patricia Quinn – or as all the unconventional conventionalists who dressed up for the occasion would know her, throaty-voiced Magenta from the planet of Transsexual, Land of Night.

Inspired by the Albert Hall’s royal connections, she told the audience of her own links with royalty. “I went back to playing in The Rocky Horror Show 21 years later,” she said, “and at the time my husband Robert Stephens was playing Lear. Yes, I know. And he received an invitation to Sandringham from Prince Charles. So Magenta hung up her fishnets and Lear hung up his crown and off we went.

“Robert found out Charles was going to be in Sheffield at the same time I was playing in Rocky Horror there, and tried to persuade him to go. The Prince said to me after, ‘Frightfully sorry Pat, but I couldn’t very well turn up in garters and fishnets.’ I said to him, ‘You could have turned up as Brad the nerd!’

“Tomorrow is the Prince of Wales’s birthday, so I sent him a card covered in lips which said, ‘Put on your fishnets tonight and come on down to the Royal Albert Hall.’ So, can we do a search of the Royal box? [Looking up] Ooh, nice calves, sir!”

Prince Charles wasn’t really in the Royal box. But I was.

When it all began, I was a regular Frankie fan: I’d sneak off in my teens to the midnight screenings in Ottawa and then New York where audiences would squirt water in the rain scene, and hurl toast across the cinema when Frank N Furter announced “a toast to absent friends”. And now, in one of those dreams/reality confusions that perplexed Dougal in Father Ted, there I was up in the box with Lady Pat and her famous friends (see main picture caption), including Adam Ant and Michael White, the maverick producer and original backer of The Rocky Horror Show – frail following another stroke but stubbornly waving away all offers of a wheelchair, and getting the biggest cheer of the night.

When it all began, I was a regular Frankie fan: I’d sneak off in my teens to the midnight screenings in Ottawa and then New York where audiences would squirt water in the rain scene, and hurl toast across the cinema when Frank N Furter announced “a toast to absent friends”. And now, in one of those dreams/reality confusions that perplexed Dougal in Father Ted, there I was up in the box with Lady Pat and her famous friends (see main picture caption), including Adam Ant and Michael White, the maverick producer and original backer of The Rocky Horror Show – frail following another stroke but stubbornly waving away all offers of a wheelchair, and getting the biggest cheer of the night.

Andrew Logan was there, too. He created the Alternative Miss World, which Marcus Campbell Sinclair is making a documentary about, as well as a doc about the last days of Logan’s famous Glasshouse home/studio (“Like” the Facebook page here). When I spoke to Logan’s partner Michael, he recalled how the Alternative Miss World launched the year before The Rocky Horror Show. “Together we changed the world,” he said, which sounds like a large boast, until you recall that Glam Rock came out of the same creative camp. As Riff-Raff presciently put it, “Nothing will ever be the same.”

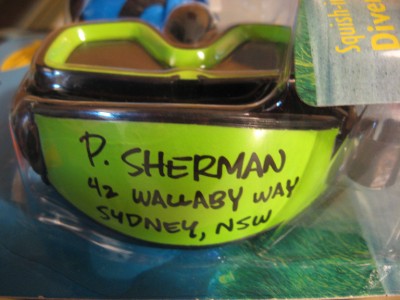

“I think perhaps you’d better both come inside.” Richard O’Brien as Riff-Raff in The Rocky Horror Picture Show

Speaking of Riff-Raff, I’ve interviewed Richard O’Brien three times, the first way back in 1987. The most recent was for The Times, in 2009, and it was a doozy. This was the first time he had discussed publicly his pain and confusion at feeling “transgender”. He cried as he described how, in the grip of near-insanity, he finally plucked up the courage to confess this to his son, only to be told, “yeah, Dad, we know”. (Presumably, The Rocky Horror Show itself gave some clue!) He’s been taking oestrogen for the last ten years, though it doesn’t stop him standing up to homophobes in the street: “You’re f***ing with the wrong drag addict!”

But there was more — a revelation that, as a lifelong Rocky Horror fan, knocked me sideways. We were talking about Frank N Furter, and what a complicated character he is. On the one hand charismatic, seductive, brilliant, talented; on the other the sort of psychopath who would kill anyone who interfered with his pleasure, and create new life only for the purpose of being his sexual plaything. It’s an astonishing post-‘60s parable – how the hippie ideals of free love and hedonism can so easily be painted black when pursued without regard for the happiness of others.

“He’s a drama queen, really,” O’Brien said of Frank. “He’s a hedonistic, self-indulgent voluptuary, and that’s his downfall. He’s an ego-driven . . . um . . .” and here his voice lowers to a stage whisper, “I was going to say, a bit like my mother.”

Wait – what was that? Is O’Brien really revealing after all these years that the inspiration for Dr. Frank N. Furter was his own mother?

Tim Curry as Frank N Furter: amazingly, inspired by Richard O’Brien’s mum

“My mother was an unpleasant woman,” O’Brien continued, with sudden venom. “She came from a working-class family: wonderful people, not much money, undereducated but honest, a great moral centre of honesty and probity. And she disowned them. She wanted to be a lady. And consequently became a person who was racist, anti-Semitic . . . It’s such a tragedy to see someone throwing their lives away on this empty journey, and at the same time believing herself superior to other people.

“She was an emotional bully. And sadly all of us, my siblings and I, are all damaged by this. She was bonkers, my mother, and I think by saying that I’m allowing her to be as horrible as she was without condemning her too much.

“I loved her, but stupid, stupid woman, she wouldn’t understand the value of that.”

I have always been struck by the passion with which Riff-Raff suddenly cries out at the end, about Frank, “He didn’t like me! He never liked me!!” It sounds like it’s ripped from somewhere deep down inside of him; gives me goose-bumps every time I see the film (and that’s close on 50 times). Now I know that Frank is inspired by O’Brien’s loveless mother, it makes heartbreaking sense.

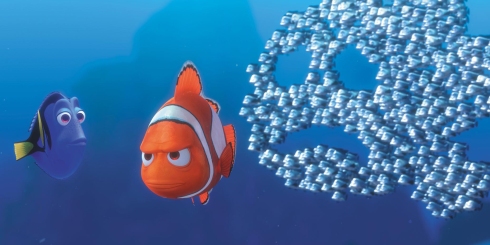

Lady Pat Stephens posing with Rocky Horror fans, plus me (second from right) and film-maker Marcus Campbell Sinclair

After the screening, a bunch of us decamped to the Royal Albert Hall’s one open bar. Marcus was a little nervous: “Pat’s going to get mobbed,” he said. And he was right. But she loved it. “Darlings, don’t you look fabulous!” cried Lady Stephens, much more welcoming than Magenta ever was, as she disappeared into a mass of fishnet stockings and maid’s outfits, and people literally ran to fetch friends and cameras.

Most of these fans were kids, barely into their twenties, who weren’t even alive in the ‘80s, let alone the ‘70s. What an extraordinary film The Rocky Horror Picture Show is, to arouse such a passionate following after all this time.

Don’t dream it. Be it.

Tags: 40th anniversary, Adam Ant, Alternative Miss World, Andrew Logan, cult, documentary, don't dream it, fan, Frank N Furter, interview, Lady Stephens, Magenta, Marcus Campbell Sinclair, Michael Davis, Michael White, mother, Patricia Quinn, Prince Charles, review, Richard O'Brien, Riff-Raff, Rocky Horror Picture Show, Royal Albert Hall, Sam Mardon, screening, speech, The Glasshouse