Who is Michael White? In The Last Impresario, the documentary about his star-cross’d and star-making life which opens in London tomorrow, and which I saw last night with a Q&A between the BBC’s Alan Yentob and the film’s young director, Gracie Otto, he is described as “the most famous person you’ve never heard of”. Otto herself hadn’t, when she attended the Cannes Film festival in 2010 as a recent film studies graduate, and noticed a mischievous, nattily dressed septuagenarian with an eye for the ladies (including herself) towards whom everyone seemed to gravitate at parties.

The more she found out about Michael White, the more convinced she became that she had the subject of her first film. White launched the careers of both the Pythons and the Goodies when he discovered a Cambridge Footlights show of unusual talent, and put it on in the West End. “It was extraordinary,” reflects John Cleese in the film. “I mean, this student show, in the West End! Unheard of. It allowed me to pay off my student debts in three months.” Bill Oddie, later of the Goodies, was another member of the revue: “Michael White was a bit like a Bond villain,” he recalls. “Always had a glamorous blonde on his arm.”

White put on Kenneth Tynan’s infamous avant-garde, fully nude erotic revue Oh! Calcutta!, which in 1970 didn’t so much push the envelope of acceptability as tear it into tiny pieces. It was only two years earlier that the centuries-old requirement for all plays to be approved by the Lord Chamberlain’s office had been scrapped. Despite (or because of) scandalised and negative reviews, the show became the longest-running in Broadway at the time.

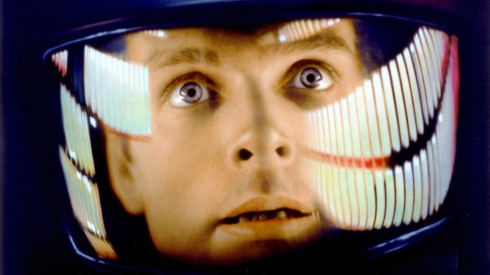

White was the first to bring Dame Edna to London, though he lost a fortune with “her” on Broadway. He made The Rocky Horror Show a hit, then signed away the rights for a song to a hard-nosed American producer while distracted by drugs and women. In film, he produced such cult hits as Monty Python And The Holy Grail, My Dinner With Andre, and Polyester by John Waters, “the Pope of Trash”. The Cannes screening was presented in “Odorama” – scratch-and-sniff cards with scents such as fart and dirty socks. Waters recalls, “They broke the glass on the doors, people were so keen to get in.”

Oh, and lest you think White had a talent only for spotting actors, during the Q&A Otto mentioned one bit she hadn’t managed to fit into the film: White once attended a dinner bringing a friend whom he predicted “would be big in computers”. The friend was Steve Jobs.

Jobs, of course, is no longer available to interview, but Otto tracked down some heavyweight talking heads in The Last Impresario. Here’s a small sample:

Anna Wintour, editor of Vogue: “He was one of those extraordinary people who seem to know everyone on the planet. He was certainly by far the first person to talk to me about Kate Moss, before any agent.”

Kate Moss, supermodel: “When we first met, we ended up talking on and on, and then it was ‘let’s go to another club’. He was the only one who could really keep up with me.”

John Waters, cult film-maker: “He wasn’t a suit. Or if he was, he always had a great one on.”

Yoko Ono, whose art show White put on in pre-Lennon days: “Michael’s an interesting guy, a visionary. Very cool and visionary.”

Jim Sharman, director of The Rocky Horror Show: “Michael was one of the few producers who were prepared to take a punt, a gamble, on risky ventures that challenged the status quo.”

But for every party, there’s a hangover. And when your whole life is a party, that’s one doozy of a come-down.

By the time Otto catches up with White, he has suffered three strokes. The second, according to Peter Richardson of the seminal ‘80s comedy troupe The Comic Strip (yes, White produced them, too), came hot on the heels of the first.

“Imagine: you’ve had a stroke, then you go out partying with Jack [Nicholson, natch]. Jack saved him, I think, and got him to the best hospital.”

White is also broke, and somewhat tearfully packing up his memorabilia for sale at auction. In particular he has an extraordinary collection of 30,000-odd candid pics of the stars (see above) – at any social function, he’d be snapping away. An ex-partner felt it was his way of dealing with people, keeping them close and yet simultaneously at arm’s length. Sent to a boarding school in Switzerland at seven to cure his asthma, he was terribly lonely. Ever since, he liked to cocoon himself in a whirl of fascinating, dynamic people, while keeping his emotions and real feelings to himself.

In the end, White remains a charming enigma, the calm at the heart of the storm. He is not a loquacious interview, as a result of the strokes, but he seems not much given to self-analysis anyway. Who is Michael White? This fascinating documentary gets as close as anyone is likely to.